|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

This imposing Buddha dates from the dynamic period surrounding the second half then collapse of the Ming Dynasty, and the rise of the Qing. This period spans the 15th to 17th More »

This imposing Buddha dates from the dynamic period surrounding the second half then collapse of the Ming Dynasty, and the rise of the Qing. This period spans the 15th to 17th centuries AD, and saw many of the most important developments in Chinese culture. The Ming, founded in 1368 under the peasant emperor Hong Wu, was a militarily oriented socio-political entity much given to radical interpretations of Confucianism and with a very strong defensive ethos (the Great Wall dates to this period). However by the 17th century cracks had started to appear, young male heirs being manipulated as puppets by the ruling families, and the court became rotten with intrigue. To compound matters, the Manchurian Chinese cities were being attacked by local groups dubbed the Manchus who eventually invaded China and deposed the old regime. The last Ming emperor, Chongzhen, hanged himself on Coal Hill overlooking the Forbidden City, bringing an end to his line and ushering in the Qing dynasty. The Qing was founded by Nurhaci in the early 17th century, and persisted until the collapse of imperial China in 1912 with the hapless Pu-Yi, the last emperor of China. Their isolationist policies, social control (all men required to shave their heads, wear queues, and wear Manchu rather than traditional Chinese dress) introspection and cultural conservatism was at odds with their liberality in certain social issues such as forbidding the binding of womens feet (later withdrawn due to social pressure from the populace). However, this cultural inflexibility which grew as the emperors grew increasingly unaware of the world outside their palace walls, much less the countrys borders was a difficult stance to maintain in the shadow of the European thalassocracies, and it may have been this which helped hasten the demise of the Imperial system. The Ming and the Qing dynasties were highly creative times, seeing the appearance of the first novels written in the vernacular, considerable development in the visual arts and outstanding craftsmanship in all fields. The present sculpture is a case in fact, and it is perhaps somewhat disarming to reflect that this peaceful figure dates from a period of such spectacular turmoil. This superb sculpture admirably portrays the Vairocana Buddhas poise and serenity. He rests in padnasanam (lotus) position, his hands folded together in a palms-up position known as dhyana mudra. The face is exquisitely carved, the features carefully measured and harmoniously expressed. The face is framed by pendulous earlobes and hair pulled into a helmet-like arrangement of tiny, serrated knobs. The drapery is extremely competent in its execution, describing a roll of curved pleats running from the shoulders to the lap, the tunic-like garment encasing the arms down to the wrist and concealing the legs. The patina is perfect, and the piece is in extremely good condition. The Buddha in sharp contradistinction from the more ornate Bodhisattva figures is plain and unadorned, reflecting the simplicity and purity of the Vairocana Buddhas character. Indeed, the lack of ornamental detailing increases the sensual impact and clean lines of this remarkable carving. This is a truly wonderful piece of ancient sculpture. - (X.0708) « Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg)

Price :

Contact Dealer

The M’ing dynasty was one of the most important in China’s long history. It saw the toppling of the Y’uan Mongol empire under Hong Wu, the third of only More »

The M’ing dynasty was one of the most important in China’s long history. It saw the toppling of the Y’uan Mongol empire under Hong Wu, the third of only three peasants ever to become emperor in China. The leader of the peasant revolt that ushered in the M’ing dynasty, Hong Wu was an extremely brutal, ruthless dictator, whose creed was one of rabid Neo- Confucianism combined with a militaristic sense of China’s destiny and organisation. The one aspect of Confucius’ learning that he ignored was that declaring military institutions to be inferior to intellectual elites, and that the former should be in the latter’s thrall. A great deal was therefore spent on expanding the army, consolidating defences against attack by the Mongols and neighbouring groups, and in major defensive architecture – notably the Great Wall.Perhaps reflecting Hong Wu’s own humble origins, the economy came to emphasise agriculture over trade (which Confucianism deemed to be vulgar and parasitical), and provided safeguards for peasants. Negative outcomes included enormous inflation and devaluation of money and resultant social unrest. However, this period also saw enormous cultural strides, including the development of the novel, the introduction of duotone blue/white ceramics and a plethora of artistic and religious developments. The eventual collapse of the M’ing Dynasty was in part triggered by internal dynamics but was primarily induced through the influx of ultra-conservative Manchurian nomads (Manchu) who founded the Q’ing dynasty in 1644. This long-lived dynasty (ending in 1912 with the hapless Pu-Yi) consolidated China’s imperial standing, while cementing the Emperor’s status as a living god and inducing a strong introspective element of Chinese culture that did a great deal to isolate the cultural behemoth from the rest of the world.The current sculpture dates from this highly changeable and dynamic time. This imposing wooden sculpture depicts the universal (Vairocana) Buddha seated in padmasanam (lotus position) and the hands folded together, palms up, in a meditative position known as dhyana mudra. The Buddha is bare-chested and wears a pantaloon-like garment, tied at the waist with an ornate knot, and overlain with a loose, flowing tunic. He wears a very impassive, reflective and serene expression. The hair is finished in high relief spikelets with the supra-cranial eminence – believed to denote Buddha’s wisdom and learning – marked out clearly in the central aspect of the head. The earlobes are long and pendulous, framing the face in collaboration with the complex hairstyle. The quality of the drapery carving is extremely high, with elegant curves and pleats carefully yet languidly rendered. Traces of lacquered polychrome paint suggest that the figure was originally brightly coloured, although the bare wood is perhaps a better reflection of the Buddha’s placid, wise and wholesome character. The quality and condition of this Buddha are stunning. In terms of aesthetic and social value, this is a truly exceptional specimen that would be the star of any context into which it were placed. - (X.0713 (LSO))

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

Bronze working is believed to have developed in China without the influence of outside cultures around 2000 B.C. Although there was initially numerous centers of bronze More »

Bronze working is believed to have developed in China without the influence of outside cultures around 2000 B.C. Although there was initially numerous centers of bronze technology, the area in contemporary Henan Province along the banks of the Yellow River eventually advanced to become the most important and influential cultural center of early Bronze Age China. An alloy of copper and tin, bronze was used to create weapons, horse bits and chariot parts, and ritual vessels. China was the only Bronze Age culture in the world to utilize the piece-mold casting method. The advantage of this technique, which involved the use of terracotta molds that were broken into smaller pieces before firing and then reassembled before casting, was that it allowed sculptors to achieve more intricate designs that were more sharply defined.The Shang Dynasty is the first recorded kingdom in Chinese history. While no major texts have survived, examples of their pictogram writing have found found engraved on bronze vessels and oracle bones. According to legend, the dynasty was founded by a rebel hero who overthrew that last ruler of the corrupt Xia Dynasty. The Shang kings ruled over much of northern China and were engaged in frequent battles with nomadic tribesmen that roamed the steppes and other neighboring tribes. Their society was based primarily upon agriculture, supplemented by hunting and animal husbandry. The Dynasty switched capitals a number of times, although the city Jin, near modern-day Anyang, became the largest and most important.This glorious utensil surely would have been a treasured possession. However, this yan was not interred with its owner as a sign of wealth. Instead, this steamer was expected to continue cooking meals in the afterlife. The Ancient Chinese believed that the afterlife was an extension of our earthly existence. Thus, it seems logical to reason that as we require food to nourish our bodies on earth, we will require food to nourish our souls in the afterlife. This Yan was created to steam eternally, ushering the deceased into the next world. The bountiful feast that this yan symbolizes continues throughout eternity. Today, we marvel at this work both for its historical and cultural significance as well for its overwhelming beauty. - (H.1093)

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

Upon leading a victorious rebellion against the foreign Mongul rulers of the Yuan Dynasty, a peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang seized control of China and founded the Ming Dynasty More »

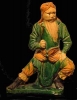

Upon leading a victorious rebellion against the foreign Mongul rulers of the Yuan Dynasty, a peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang seized control of China and founded the Ming Dynasty in 1368. As emperor, he founded his capital at Nanjing and adopted the name Hongwu as his reign title. Hongwu, literally meaning “vast military,†reflects the increased prestige of the army during the Ming Dynasty. Due to the very realistic threat still posed by the Mongols, Hongwu realized that a strong military was essential to Chinese prosperity. Thus, the orthodox Confucian view that the military was an inferior class to be ruled over by an elite class of scholars was reconsidered. During the Ming Dynasty, China proper was reunited after centuries of foreign incursion and occupation. Ming troops controlled Manchuria, and the Korean Joseon Dynasty respected the authority of the Ming rulers, at least nominally.Like the founders of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.- 220 A.D.), Hongwu was extremely suspicious of the educated courtiers that advised him and, fearful that they might attempt to overthrow him, he successfully consolidated control of all aspect of government. The strict authoritarian control Hongwu wielded over the affairs of the country was due in part to the centralized system of government he inherited from the Monguls and largely kept intact. However, Hongwu replaced the Mongul bureaucrats who had ruled the country for nearly a century with native Chinese administrators. He also reinstated the Confucian examination system that tested would-be civic officials on their knowledge of literature and philosophy. Unlike the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.), which received most of its taxes from mercantile commerce, the Ming economy was based primarily on agriculture, reflecting both the peasant roots of its founder as well as the Confucian belief that trade was ignoble and parasitic.Traditionally in Chinese art, representations of civic officials symbolized the order of government. However, this gorgeous sculpture of a civic official, created during the Ming Dynasty, symbolizes more than mere government, it symbolizes the return of the ethnic Chinese to power. Aesthetically, the work recalls similar depictions of civic officials created during the T’ang Dynasty, a golden age of Chinese culture. Surely this visual link to the glories of the past is not unintentional. This official stands upon a substantial base, revealing his revered position within society. He is no mere administrator; he is the embodiment of the will of the Emperor. An elegant robe with long overflowing sleeves frames his body. The tall cap with a chinstrap marks his official status. His facial features and groomed goatee reveal his native Chinese ethnic origins. Remnants of the original pigment that once covered this work are still visible, including orange highlights on the robe and black on his facial hair, cap, and shoes. - (H.1094)

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

The Ordos culture refers to groups of nomadic peoples that inhabited the southern Mongolian Plateau as early as the Shang Dynasty. Though they lived along the western and More »

The Ordos culture refers to groups of nomadic peoples that inhabited the southern Mongolian Plateau as early as the Shang Dynasty. Though they lived along the western and northern perimeters of the main Han Dynasty settlements, they retained a distinctive culture more alligned with the Scythian peoples of the Steppes than their Chinese neighbors. They are known primarily through their metalwork. Many of the belt plaques, horse gear, and weapons that have been found depict scenes of animals in combat. Such themes are linked to the ancient Near Eastern tradition. During the Han Dynasty, the Chinese formulated peace treaties with the Xiongnu peoples who were the dominent force of the Ordos region at this time. Xiongnu tombs have been excavated in Mongolia that contained Chinese luxury goods such as silk and bronze mirrors next to their own bronze works. This bronze belt plaque is a perfect example of the Ordus style. A scene depicting a pair of animals in combat decorates the front. A mythological beast that may well be a dragon attacks what appears to be a ram, biting it on the neck. It is likely that this work was originally gilt, though the surface now has a lovely patina that testifies to its age. - (LO.616) « Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

The Liao Dynasty was founded by nomadic Qidan tribesmen, possibly an offspring of the 5th century Xianbei people, in 907 A.D. At its height, Liao territory comprised much of More »

The Liao Dynasty was founded by nomadic Qidan tribesmen, possibly an offspring of the 5th century Xianbei people, in 907 A.D. At its height, Liao territory comprised much of modern Manchuria, Mongolia and the northeastern corner of China. After the establishment of the Song Dynasty in 960 A.D., a border war between the two dynasties ensued. After a series of decisive victories, the Liao armies began to approach the Song capital when a compromise was reached recognizing the authority of the Liao in parts of northern China. An annual tribute to the Liao was agreed upon and a period of peace and stability between the two Dynasties followed. Commercial and cultural links forged during this year exposed the Liao to many influential Chinese customs. However, the Liao maintained many of their native traditions. The Liao Dynasty came to an end after one of their subjects, the Juchen tribe, rose up with the aid of the Song, overthrew their masters and established the Jin Dynasty in 1125 A.D.Preservation of the physical remains of the deceased was a central focus of the funerary rites of the Liao. The corpse served as a sanctuary for the spirit of the dead and was carefully preserved for post-mortem immortality in the afterlife. To achieve this goal, the tomb’s occupant was encased in a metal-mesh vest, his feet covered with metal boots and his face covered with a metal sheet mask, which according to the rank, could range from bronze to silver and gold. Indeed, the same custom of placing a face mask over the dead represented a long-standing tradition among the nomadic tribes inhabiting the borderland of northern China, since the Bronze Age period, influenced by similar practices in ethnic groups from north and north-east Asia such as the Scythians, and was later enriched with Daoist and Buddhist religious connotations.One of the richest tombs yielding beautiful gold masks, similar to the one here illustrated, belonged to Princess Chen and her consort. One of the fewest unspoiled Liao burials to date, Princess Chen’s tomb was unearthed in 1986 at Qinglongshan, Naiman Qi in Inner Mongolia. It was indeed a very elaborate burial that could have only been afforded by the wealthy elite. Still it provides an unparallel account on Qidan burial practice. According to Qidan customs, the deceased was placed in the rear chamber on a painted brick pedestal (guanchuang) without a coffin, the top of the pedestal paved with cypress slips and covered by a canopied textile curtain. The wooden interior of the rear chamber probably imitated the traditional felt yurt of the Qidan people, while the masks and silver-meshes covered the corpse, further ornamented with jades, ambers and beautiful silk kesi textiles.Our mask, instead, was made of thin bronze metal sheet, repoussed into shape, and later gilded, and possibly belonged to an official of middle rank. The facial features of the mask are simple yet hauntingly evocative: prominent arched brows meet at the bridge of the inverted T-shaped nose. The eyes are narrow, as if squinting, the mouth rigid and tense. Judging from the archaeological evidence, also this mask –like those found in Princess Chen’s tomb- would have been placed on the face of the deceased and ornamented further with colourful fabrics and personal accessories, now lost forever.Reference: Gold face mask belonging to Princess Chen, Tomb 3 at Qinglongshan, Naiman Qi, Inner Mongolia in Yang Xiaoneng, Chinese archaeology in the Twentieth Century, Yale University press, 2004: pp. 459-461. And Nei Menggu Kaogu Yanjiusuo, Liao Chenguo gongzhu fuma hezang mu fajue jianbao, Wenwu 1987.11: 4-24 And Liao Chenguo Gongzhu Mu, 1993. - (LA.512)

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

The earliest depiction of houses, going back to the Neolithic period, were modelled in ceramic. Before the Han period, such models more often consisted of a single More »

The earliest depiction of houses, going back to the Neolithic period, were modelled in ceramic. Before the Han period, such models more often consisted of a single cylindrical chamber with a roof, but during the Han dynasty designs of much more complex architectural complexes appeared throughout the country. Especially from the 1st century AD, tomb mingqi production expanded to include new types of artefacts, ranging from everyday tools to figures of domestic animals and architectural models. Tombs in Henan, Shanxi, Shaanxi and Gansu provinces have yielded a large quantity of architectural models featuring multi-storey buildings with overhanging roofs, brackets, pillars, ornamental balustrades, latticework windows and hinged doors. The majority was lead-glazed in sparkling colours including green, yellow, brownish and black, but unglazed painted examples are also known, especially in Sichuan.Such models and other miniature or non-functional objects are collectively known as ‘mingqi’ (spirit articles) and have been traditionally interpreted as surrogates for objects of value placed in the tomb. Yet recent archaeological evidence have highlighted that these objects might have instead constituted an integral part of the strategy to recreate the earthly dwelling of the deceased. The replication of the living world and its constituents within the tomb might have been induced by various ideological factors, including a new religious trend emphasising the separation of the dead from the living and other material manifestations of different philosophical ideas, but also possibly by the effort to reproduce a self-sustaining version of the world- a fictive and efficacious comprehensive replica, made up of both real sacrificed humans and animals (the 'presented') and elements such as the multi-storey house (the 're-presented').Daily life has thus been vividly ‘reproduced’ by capturing in a still image the various figurines peaking out from the house balconies and doors: look at the matron hieratically standing at the entrance door, holding a fan and looking towards his labourers to her right, either washing, holding a winnowing fan or a sickle, or again, at the archer perilously leaning outward on the balustrade of the third floor, shooting to the sky. Traces of the original red paint are also visible under the roof and on the brackets, suggesting that the entire house must have once been colourfully decorated with draperies, providing a vivid picture of what a wealthy abode must have looked like during the Han period. Furthermore, this house is composed of three storeys, a combination rarely encountered on domestic architecture of the period (usually made of one of two storeys) and more often employed in the depiction of military outposts such as watchtowers. Its architectural details, including lattice windows and bracketed pillars are extremely well preserved, as well as the upturned tiles on the overhanging roof, thus providing an indelible picture of this long-gone archaeological past.TL tested. - (LA.516)

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

Origin: China Circa: 1368 AD to 1644 AD Dimensions: 17.25" (43.8cm) high Collection: Chinese Art Style: Ming Dynasty Medium: Glazed Terracotta

Origin: China Circa: 1368 AD to 1644 AD Dimensions: 17.25" (43.8cm) high Collection: Chinese Art Style: Ming Dynasty Medium: Glazed Terracotta

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

An exquisitely sculpted grey basalt torso of a Bodhisattva (‘enlightened being’) standing frontally with legs joined on a low pedestal. He holds a jar with lotus More »

An exquisitely sculpted grey basalt torso of a Bodhisattva (‘enlightened being’) standing frontally with legs joined on a low pedestal. He holds a jar with lotus buds between his palms at chest level. The outer robe, known as the sanghati, covers both shoulders and descends in delicate folds. The monumental scale of the statue allowed the sculptor to carve the drapery and scarves in fine detail.The Khitan were an ancient nomadic tribe that lived in north-eastern China. The name ‘Liao’ comes from the valley of the Liao river where they originally lived. They were brought under Chinese rule during the Tang dynasty. In 907 AD when the Tang collapsed, a Khitan chieftain established the empire of Liao. They ruled north- eastern China contemporaneously with the Five Dynasties and later with the Northern Song. The Liao were important patrons of Buddhism. The pacifism of Buddhism and the assimilation of Chinese wealth and cultural elements gradually weakened the Liao’s once-military character. In 1125 AD the Song army annihilated the Liao. - (LA.541)

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price :

Contact Dealer

Pair of sculptural standing Avalokitesvara bodhisattvas, the high mukuta crowns, each bejewelled with either a small Amithaba icon, or the sacred bottle, one hand raised in More »

Pair of sculptural standing Avalokitesvara bodhisattvas, the high mukuta crowns, each bejewelled with either a small Amithaba icon, or the sacred bottle, one hand raised in vitarka mudra, the other one softly opened with palm up, the bodies slightly bent in tribanga pose, the bare chests with an ornate necklace, flowing garments reaching the feet and partly covering them. Traces of the original lacquered pigmentation remain.The confession of the Great Vehicle, Mahayana (chin.: Dasheng), spread from Kashmir, Gandhara, Sogdia and Inner Asia into China, and further to Korea and Japan. It teaches that salvation is possible to all sentient beings because they possess the Buddha nature in them and hence all have the potentiality of being enlightened. Enlightenment is simply achieved by faith and devotion to Buddha and the religious ideal, the Bodhisattva (chin.: Pusa), Pratyekabuddha (chin.: Pizhifo) or Arhat (chin.: Aluohan, short: Luohan). These beings, though qualified to enter nirvana, delay their final entry in order to bring every sentient being across the sea of misery to the calm shores of enlightenment.Avalokitesvara ("Observing the Sounds of the World", chin.: Guanshiyin, short: Guanyin, or Guanzizai), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, is one of the most venerated icon of the Buddhist Pantheon. In this case, the two mirror images would have been placed to the side of the main Buddha as his flanking attendants, in the main temple hall. - (LA.559)

« Less

|

|

Ancient Asian

|

|

|

|

|

| Vendor Details |

Close |

| Contact Info : |

| Barakat Gallery |

| 405 North Rodeo Drive |

| Beverly Hills |

| California-90210 |

| USA |

| Email : barakat@barakatgallery.com |

| Phone : 310.859.8408 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|